Micro Mezzo and Macro Social Work Perspectives

Micro Mezzo and Macro Social Work Perspectives

According to the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics, the mission of the social work profession in its purpose of well-being for all is rooted in six core values. Throughout the social work profession's history, the six values are service, social justice, dignity and worth of the person, importance of human relationships, integrity, and competence. Within the constellation of these core values, there are ethical principles which stem from them and guide professional social workers when engaging with individuals, groups, and communities, as well as principles that guide policy and promotion of societal change (National Association of Social Workers, 2021).

For example, the core value of service aligns with the generalist perspective that values commitment to serving others, encouraging social workers to serve clients using a wide variety of evidence-based practices and empowering clients based on their capabilities through a strengths-based approach (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, 1.01).

Social justice in generalist practice addresses individual and systemic racism, inequalities, and inequities, while advocacy from the strengths-based approach emphasizes clients' cultural strengths and promotes equity and opportunity for marginalized or oppressed communities (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, 6.01).

Dignity and worth of the person in generalist practice respects each client's unique needs and considers multiple factors such as past traumas, cultural traditions, and strengths. The strengths-based approach emphasizes their cultural strengths, resilience, and empowerment, allowing future social workers to focus on their strengths and potential for empowerment (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, 1.02).

Importance of human relationships: The generalist perspective values micro, mezzo, and macro levels of collaboration with clients and communities (Fricke, A., 2021, June 1, para 3); alongside the strengths-based approach that reinforces support systems and encourages community and advocacy to reduce isolation (National Association of Social Workers, 2021).

Integrity aligns with generalist practice through transparency and ethics, while the strengths-based approach supports rapport during the engagement and assessment process to build empathic, honest, and respectful collaboration with clients, focusing on strengths (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, 5.01).

Competence aligns with generalist practice through the use of person-in-environment perspectives, ongoing training, and relevant knowledge, as well as evidence-based methods such as a strengths-based approach to effectively highlight clients' strengths (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, 1.04, 1.05, 4.01, 5.02).

According to Dr. Aikia Fricke of Ferris State University, Michigan, the generalist perspective in social work introduces future social workers to a broad, foundational view of considering multiple levels of practice: micro, mezzo, and macro, to address social issues and uphold the core mission of the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics, 1.01 Commitment to Clients, which prioritizes a social worker's purpose in client well-being. However, in cases where clients pose a harm to themselves or others, a social worker's responsibility to society (macro) and legal obligations may supersede loyalty to clients (National Association of Social Workers, 2021, 1.01).

The premise of the generalist perspective and strengths-based approach is to emphasize well-being by addressing challenges at biopsychosocial levels, from the individual (micro) to the societal (macro). It is important to note that the National Association of Social Workers Center for Workforce Studies found that only 2.8% of social workers are employed in macro-level careers in ‘civic, social, advocacy organizations, and grant-making and giving services’ settings, while 39.8% of social workers are employed in ‘social assistance’ mezzo social work settings (Krings, A., et al., 2020).

According to Michael Dennis Saleebey, DSW (1936-2014), professor at the University of Kansas and creator of the strengths perspective, the strengths-based approach to case management for people with severe mental illness has been well-established, extending to practice with other client groups such as individuals and groups with addictions, disadvantaged youths, communities and schools, the elderly, and other marginalized or oppressed communities (Saleebey, D., 1996, para. 2).

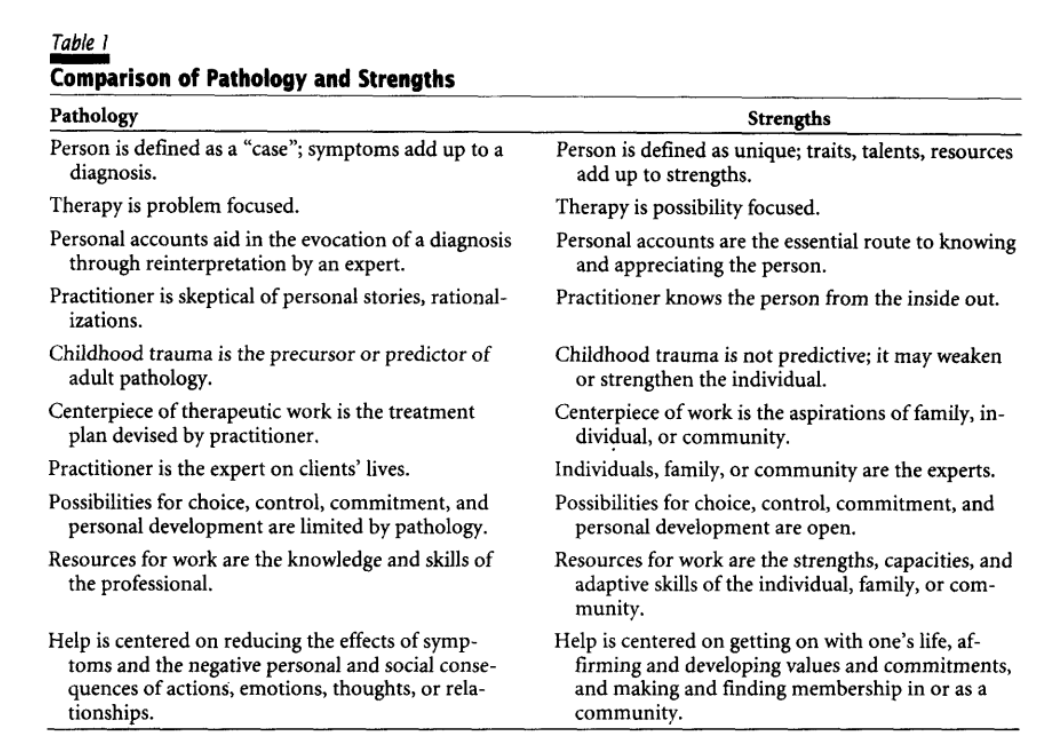

An example of how the generalist approach can be applied if I were working in domestic violence victim advocacy, I might conduct micro-level work by helping clients log stalking behaviors, maintaining detailed case notes of behaviors disclosed during meetings, and engaging in survivor-centered safety planning that considers both emotional and physical well-being. Mezzo-level social work might involve community-based response models to improve justice and advocacy for the safety of victims and survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV) and family violence (FV). Macro-level social work could include advocating for changes to state laws and policies to incorporate stalking behaviors as criteria for obtaining and enforcing protection orders or lobbying for legislative changes that promote safer communities against domestic violence, stalking, and human trafficking (Nichols, A. J., 2020). The strengths-based approach comes from a culturally sensitive view within the U.S. psychosocial tradition, emphasizing strengths rather than focusing on individual, family, and community pathology, deficits, problems, victimization, and disorder. The strengths-based perspective serves as a philosophical foundation or lens through which social workers view clients, emphasizing the belief that every individual, family, and community has strengths, resources, and potential, even in difficult situations. For example, Dr. Saleebey states that a strengths-based perspective refocuses individuals, families, and communities through the lens of their capacities for handling challenges, talents, competencies, possibilities, visions, values, and hopes that may be difficult to see due to trauma or oppression (Saleebey, D., 1996, pg. 297, para. 5).

References

Buchanan, A.M. (2024). Module 2, Discussion 1: Ethics, Values, and Morals. Touro University.

Farkas, K. J., & Romaniuk, J. R. (2020). Social work, ethics and vulnerable groups in the time of coronavirus and COVID-19. Society Register, 4(2), 67-82. https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/sr/article/view/22508/21400

National Association of Social Workers. (2021). Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. https://www.socialworkers.org/about/ethics/code-of-ethics (click on “Read the Code of Ethics online”)

Racovita, L. (2023, January 3). Moral foundations of professional ethics [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Ah7v-dL4cw0 (23:51)

Social Mettle. (n.d.). Personal and professional ethics: 4 points of difference explained. https://socialmettle.com/difference-between-personal-professional-ethics