Why are some narcissists unmotivated? Understanding the Relationships between Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Why are some narcissists unmotivated?

Although some people with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) can and do have successful careers, some may not have ambition in their life goals or have any desire to better themselves. Without having emotional (affective) empathy (other than for themselves), or the ability to have self-awareness to improve, they often lack the capacity to develop deep, meaningful relationships or grow. But what happens when someone, like a person with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), doesn’t seem to fit into the typical understanding of motivation? Through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT), we can use this framework to understand using evidence-based research why people with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) lack ambition and spend their lives not improving their situation.

Understanding Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD)

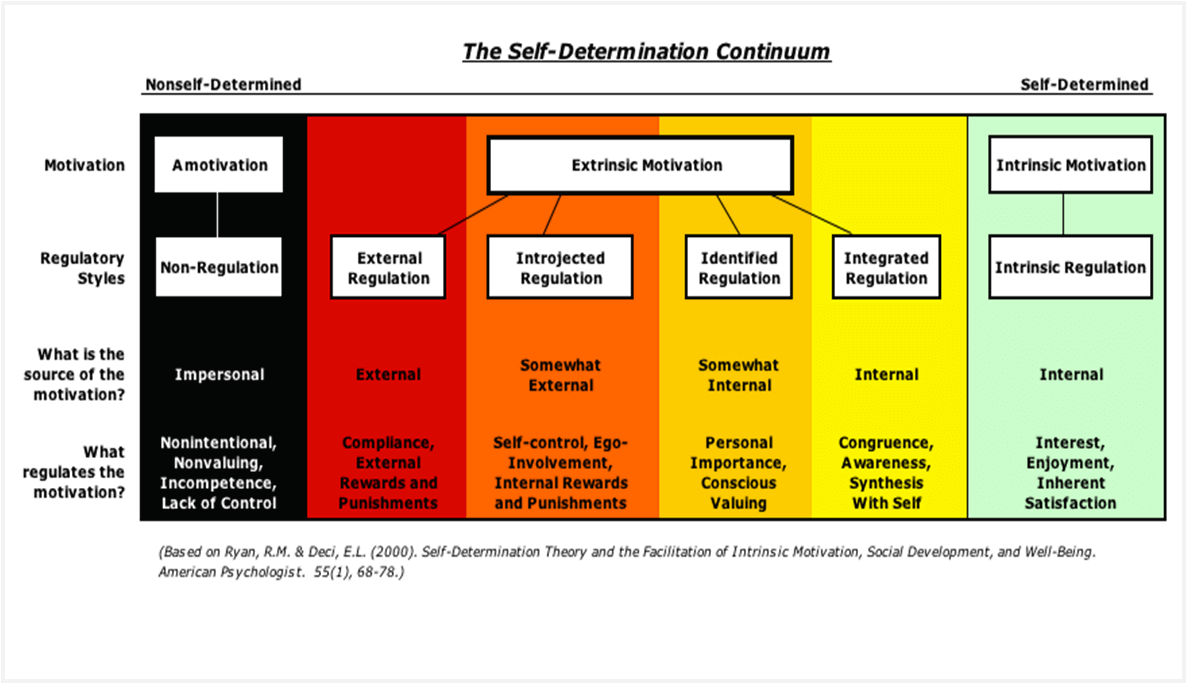

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a psychological framework developed by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan that explores human motivation, behavior, and optimal functioning. According to SDT, there are two main types of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic, both of which significantly influence who we are and how we behave. Let’s break down SDT and look at how it applies to individuals with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD).

The Basics of Self-Determination Theory (SDT): Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

At the core of SDT are the concepts of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation comes from within—it's the drive to engage in activities because they are inherently enjoyable, fulfilling, or aligned with one's core values.

Extrinsic motivation is driven by external rewards or pressures, such as grades, employment performance evaluations, praise, or approval from others (e.g., parents, family members).

Autonomous motivation when individuals feel self-directed and aligned with their own values.

Controlled motivation where behaviors are influenced by external pressures or a desire to avoid guilt or shame.

This distinction helps us understand how motivation can feel either empowering (autonomous) or pressured (controlled).

Amotivation and Narcissism

People with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD) often display behaviors that align with amotivation, a term in SDT that refers to a state where individuals feel little to no drive or desire to engage with the world. This is often seen in people who seem disengaged from meaningful goals, are resistant to change, or exhibit apathy. In the case of my ex, he self-identified as "lazy" and had little ambition to strive for goals that many people might consider fundamental-such as advancing in his career or starting a family.His tendency to reject traditional success markers-like having children or becoming a father-stemmed from the belief that they would lead to a life devoid of personal joy. This reflects the avoidance of responsibility and a deep-seated disconnection from the inherent value of personal growth and contributions to others. In this sense, amotivation is a coping mechanism for those who feel disillusioned or disempowered by external demands.

The Role of Controlled Motivation in NPD

For individuals with NPD, motivation is more likely to come from introjected regulation, a form of controlled motivation.

Introjected regulation occurs when individuals are driven by internalized values, but these values are not fully integrated into their identity. Instead, they are motivated by a desire to protect their ego, avoid feelings of shame, or seek validation. When there is a disarray of internal values (e.g., they may verbally express their values yet their actions do not match their words) narcissists may turn to maladaptive coping mechanisms by finding motivation through other ways (e.g., advancing levels endlessly in videogames, or sticking to simple things that they can do without self-improvement).

For instance, my ex’s refusal to follow in his father’s footsteps as a "workaholic" reflects a form of introjected regulation. He didn’t want to adopt what he perceived as a life of sacrifice and exhaustion, but his decision was still shaped by the internalized judgment of his father’s lifestyle; rather than a deeper, intrinsic sense of what he truly valued. This form of regulation can lead to a disconnection from authentic desires, as it’s not entirely driven by the person’s true interests or values, but by fear of becoming something they resent.

This is a common trait in NPD. The individual may reject certain societal norms not out of a conscious choice to pursue their authentic self, but as a means to assert superiority or a sense of control. This can manifest in avoiding responsibilities, like parenthood or career advancement, as a way to maintain a narrative of independence or "freedom" while simultaneously avoiding the vulnerability that comes with meaningful commitment.

Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness: The Three Basic Needs

SDT identifies three basic psychological needs that must be met for individuals to thrive: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These needs are vital for motivation and personal well-being. Autonomy refers to the feeling of being in control of one’s own behavior and choices. For those with NPD, autonomy can be both a source of motivation and a defensive posture. Their need to feel in control often manifests in pushing away anything that might threaten their self-image.Competence involves the desire to feel effective and capable in one’s actions. Narcissistic individuals may struggle with this, as their inflated self-image often masks deeper feelings of inadequacy. They might avoid challenges where they risk failing, as this would tarnish their grandiose self-perception.

Relatedness speaks to the need for connection and belonging with others. NPD often leads to issues in this area, as the person may struggle with forming genuine connections due to a deep-seated fear of vulnerability or a belief that they are superior to others.

In my ex’s case, he exhibited a lack of competence and relatedness in his professional life and relationships. His low-wage job and refusal to take on more responsibility were manifestations of this lack of self-worth. He avoided situations where he could potentially fail or expose himself to criticism—another key symptom of NPD.

The Narcissistic Disconnection from Intrinsic Motivation

While intrinsic motivation is key to achieving self-determination and fulfillment, narcissistic individuals are often disconnected from their intrinsic desires. They may appear to be motivated, but it’s often driven by an external need to maintain a facade of superiority, rather than an internal desire to achieve personal growth or find meaning.In the case of my ex, his rejection of fatherhood and work obligations wasn’t rooted in a deep understanding of his own values, but rather a knee-jerk rejection of his father’s model of hard work and sacrifice. His motivation was shaped more by fear of inadequacy (controlled motivation) than by a true sense of autonomy or intrinsic satisfaction.